Grandparents Are for Making Memories

Grandparents Are for Making Memories is a confluence of Dr. Lansford’s experience as a parent and grandparent with her learning in education, business, and helping people thrive.

A compelling adventure into grandparenthood with ideas and inspiration for enhancing relationship, Dr. Z makes interactions more than just treats and childcare. While exploring such issues as discipline and personalities, the chapter on fears and feelings with the strategy of how grandparents can ensure that precious grandchildren avoid life altering traps of addiction, is an essential. Whatever the age, circumstances, or family dynamics, this riveting conversation can enhance any grandparent relationship, even in a pandemic.

Click on the tabs below to read some excerpts from the book

Copyright

©2020, Zelma Lansford, Ed.D.

Spiral Publications

Atlanta, Georgia

United States of America

______________________________

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the expressed written permission of the author. This includes reprints, excerpts, photocopying, printing, recording, or any future means of reproducing text. Please direct permission requests to the author.

This book contains numerous examples from the author’s experience that are used to demonstrate the concepts. These are an amalgamation of people and situations. The names have been changed to avoid any inappropriate attention or identification.

Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors, omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. The suggestions and concepts contained herein may not be suitable for a specific situation.

ISBN: 978-0-9821833-8-0

Copyrighted Material

Chapters

- 1 Grandparent Time is for Making Memories – 9

- 2 Strong Family Bonds – 31

- 3 Grandparents’ Rules and Discipline – 71

- 4 Influence During Childhood – 104

- 5 Special Opportunities for Grandparents – 128

- 6 The Instant Generation – 182

- 7 Grandchildren’s Personalities – 219

- 8 Communicating with Grandchildren – 253

- 9 Grandparents’ Guidance for Decisions – 293

- 10 Fears and Feelings – 324

- 11 Making Memories that Make a Difference – 367

- 12 The Splendid Results – 404

The Grandparents’ Prayer

We thank you, O Lord, for the gifts of children and grandchildren.

As we thank you for each child, we give thanks for the parents, and ask your blessings on their leadership and on our relationships with them.

Guide us as we attempt to use our wisdom and experience to support the development of character and foster a love of learning.

As we strive to guard against defensiveness in the face of change, help us develop a reasonable optimism when confronted by the new.

Assist us as we appreciate and honor each child’s differences.

Prompt our words, that they may be acceptable in thy sight, and grant us insight as we endeavor to inspire their decisions.

Help us to set aside unnecessary fears, and recognize our potential for a creative response.

Please keep us ever focused on the work you have set before us, as we endeavor to live hopefully into the future.

All this we ask in the name of your child, our savior, Jesus Christ,

Amen.

From the prayerful inspirations of The Rev. William Harkins, Ph.D, Cathedral of St. Phillip; Atlanta, Georgia

Grandparents Are for Making Memories

We thank you, O Lord, for the gifts of children and grandchildren.

Grandparents are the gift that can make a profound difference in a child’s life. Grandchildren are the gifts that bring joy to the second part of grandparents’ lives. The relationship between these generations can significantly enhance both the young and the seniors.

When I began this project, it was with the metaphor of relaxing with you, the reader, at a favorite coffee shop. We’re sitting on a beautiful patio overlooking a gorgeous river scene. Beside us is a bubbling fountain surrounded by pretty flowers. It’s a serene, blue sky day when you tell me that your daughter’s romantic relationship is becoming quite intense and your son has just married. You tell me that you anticipate becoming a grandparent within the next two years. Then, you mention that your son has given you a step-grandchild who is five and one who is twelve. You add that you have embraced them, but with challenges since they live on the other side of the continent.

You ask me to tell you about my experiences and expertise on being a grandparent. I’ll share with you, not my grandparent perfection, for that I am not. Instead, I’ll share what I’ve learned, the joys my grandson has taught me, and the enormous capacity that can be generated in continuing the bond that grandparents feel when we first nestle the grandchild in our loving arms. That bond is the foundation of a relationship that can extend far beyond childhood and make a positive difference in the child’s life while bringing indescribable joy to us grandparents.

As I share what I’ve learned about this wonderful role, perhaps a good place to begin is with the end in mind—what we ultimately want to achieve. Regardless of their present age, let’s think about what it is that we want for grandchildren when they’re adults? As we consider our ultimate goals for these precious young ones, we probably use words like “happy, successful, stable, secure, of good character,” and we may include a religious description. Beginning with the end, the goal, of what we want for our grandchildren was easy for me as I reflected on some of the incredible people I’ve come to know through my work in leadership development. I’ve looked at their qualities, their skills and abilities, at how they’ve achieved success and how they’ve handled failure. From the park ranger to the chief executive of an international corporation, I’ve considered how they became who they are and how they’ve achieved such satisfying and admirable lives.

Along with my experiences of observing and working with happy, successful people of good character, I draw from my early career in teaching high school, a decade in developing and leading an elementary school, then teaching graduate students, and ultimately working in corporate America. I learned the effects of family and relationships at each age level. In contemplating this confluence of learning, I’ve found ideas to share for making grandparenting more effective and more rewarding for both grandparents and grandchildren.

Memories of Grandparents

In looking at how phenomenal the grandparents’ influence can be, let’s recall our experiences with our own grandparents. Let’s think of what we remember about them. Sometimes, our most vivid memories describe something about our relationship with them. Did you see your grandparents as often as you would have liked? Was your time with them delightful, educational, indulgent, happy? When you think of the special times with your grandparents, perhaps there are also memories of cookies, treats, stories, swimming, unique activities, or whatever made relationships with them memorable. What are your most outstanding recollections?

Are there questions you wish you’d asked your grandparents or great-grandparents— something you wish you knew about their childhoods, struggles, triumphs, and their lives? What would you like to know about the times, their school experiences, and what their lives were like as children? Think about the many things you learned from them, or wish you could have learned from them? Go beyond the trips, the activities, the stories, and the family celebrations you enjoyed with your grandparents. Think about how they talked to you and how they made you feel. How did they influence the person you are today—your character, likes and dislikes, your hobbies and interests?

Perhaps you knew how much they loved you, not only because they told you, but because of the way they treated or interacted with you. If you were fortunate enough to have seen them often and have a close relationship with them, they probably made you feel very special. Think about how they communicated unconditional love to you—or the kind of expression of love that you wanted. Certainly, we recall the treats and the activities, but for some of us, our most prominent memories are about the relationships and how grandparents made us feel.

If you didn’t have an ideal relationship with your grandparents, or they lived at a distance, you may share my grandmother’s feelings. Unfortunately, her grandparents all died before she was born, but I remember her talking about how her friends at school would bring big cookies that their grandmothers had made and were always telling about their grandparents. She talked about deciding that if she ever became a grandmother, she would be a very good one—and she was! She made beautiful memories, just as we can, regardless of whether our experience was ideal—or not so memorable.

If you didn’t know your grandparents, or perhaps you were unable to enjoy a relationship with them, what did you miss? Describe how you would have like the time with them to have been, the kinds of activities you would have enjoyed doing with grandparents, and how you would have wanted them to feel about you. In thinking about these relationships, let’s consider:

When our grandchildren are age 60, what do we want them to remember about us? What is it that’s so memorable about our own relationships with our grandparents? What do we want our grandchildren to value, as we treasure memories of our grandparents?

What kind of impact will we have made on their lives?

How will they be better because of our relationship with them?

Of course, grandparents generally want to be loved, respected, and appreciated. We want our precious grandchildren to have warm, fond memories of us. We want them to remember what they learned from us and realize the importance of their relationship with us.

If I do my job well, by the time you get to the end of this little book, you’ll have some new ideas about what your grandchildren will remember about their time with you and be even more aware of the influence that you can have in their lives. My intent in this conversation is to increase awareness of how much more we can enable grandchildren to remember. We’ll look at how we can extend our influence to make a major difference in their success as happy, stable, citizens of good character who contribute to society. In addition, maybe we can think about how we will feel when our grandchildren are teens and adults and we can see the result of our positive influence.

Naturally, there will be some indulgences of treats and gifts in our relationships with grandchildren. Maybe that’s part of the grandparent role, but our capacity can extend far beyond treats and child care. Our influence can help to shape the person that the child will become.

Becoming a Grandparent

In an ideal world, our adult children meet their prince or princess after they’re mature, have a stable career, are financially secure, and are ready to make a lifetime commitment. Yes, that’s how families begin in an ideal society, but our changing social norms may promote a different arrangement. Today’s adults may choose a mate of the same gender, become a single parent, or they may not choose to marry before having children. Their choices, and our lack of control over their choices, often contribute to conflicts between parents and the adult children.

Young people aren’t always aware that the results of their decisions may have a major impact on prospective grandparents. We’ve invested considerable time, money, and much of our lives in our children, we’ve sought the best of everything for them, from education to Christmas presents. When it comes to the choice of a mate, however, we may not always deem the timing to be right or the prospective son or daughter-in-law worthy of our precious child. Although we may hope for a different relationship, or a different mate for them, we must acquiesce and recognize that this is a decision that is not ours to make. Even when we’re certain that we could improve on the decision, we must realize that in the U.S. culture, we’re not in charge of choosing our adult children’s relationships.

We can, however, initiate diplomatic discussions. We can invite these young people to look at all sides of the issue and explore the unintended consequences. We can have conversations, attempt to guide and coach, then lament in private; but we cannot make the decisions for them. Although we can’t be too aggressive with our reservations about their choices, perhaps, we can enhance their decision making or diplomatically plant some seeds of doubt with some of the carefully chosen question in Chapter 12. Sometimes, we’re thrilled with our offsprings’ right decision making, but occasionally, we must simply accept and make the best of it.

After the mate has been chosen, the couple is committed and have children, however, the time for our guidance or attempted negotiation is over. Our job becomes to make the best of everything and adapt to this new member of the family, accepting him or her as is. Constant criticism or sarcastic jabs will not enhance family relationships. The beginning of a great relationship between grandparents and grandchildren begins, if possible, with bonding with our child’s spouse/mate/partner. Our best course is to support, encourage, and build a strong relationship with the chosen one of our adult child, even if there are aspects that are unappealing to us. The best foundation for our grandchildren will be the parents’ healthy relationship.

We adults are usually happiest when we feel in control of our own lives and are able to make the major decisions that affect our lives. Typically, however, becoming a grandparent is not a decision that we can make. Oh, we may talk about how wonderful it will be to have grandchildren, and we eventually become excited, but it’s frequently an anticipated event that’s an announcement from our adult children—not exactly a choice possible for us to make. Yet, in many ways, it’s a life-changing decision that someone else is making for us. For the first-time grandparent, it can be daunting as we think of the enormous responsibility and expectations that might be thrust upon us. We may be excited or frustrated at the timing, but nevertheless, it’s a new addition to our family, a new role, and a new experience.

I recall the Mothers Day lunch when, in the midst of my daughter and son-in-law’s accolades about what a devoted mother I’d been, my son-in-law asked how I felt about being a grandmother. I quipped something sarcastic about not being the gray-haired nana type because I was too busy traveling and doing exciting work. The perplexed look on my daughter’s face led me to quickly add that I would love being a grandmother, but maybe I’d just avoid the image. Looking relieved, she said, “Good, because guess what you’re getting for Christmas!” Of course, I was happy for them, but at the time, no one gave thought about what it would mean for me. Yes, regardless of how much or how little involvement we have in our grandchildren’s lives, we’re not usually part of the decision, but we accept it joyfully the first time we hold that adorable infant. Even though it may present challenges, unanticipated responsibilities, and even hardships, somehow, grandchildren make it all worthwhile.

(Pages not included here)

Summary

Although grandparenthood is often announced and thrust on us with the assumption that we will love the role, it’s a grand opportunity, regardless of other circumstances. We can vastly improve our effectiveness and the satisfaction that we derive if we are thoughtful, informed, and intentional in our approach. By looking at this opportunity with a long-term view—aware of our ultimate goal—rather than just a visit, a burden, or baby-sitting, we can markedly extend our influence. The satisfaction that we derive from the grandchildren, and our highly influential relationships can help to shape their character and contribute to their success.

Becoming a grandparent can produce enormous joy, pleasure, stress, resentment, and a plethora of emotions. It can create a whole new bond with our adult children, or become the basis of a new set of conflicts. Resolving our own feelings, however, we can become a source of solidarity for our families. We can be the caring, reliable adults who are a positive influence and constant source of unconditional love and support for the grandchildren. We can make a significant difference in our grandchildren’s entire lives.

We can “plant seeds” for character, stability, success, and goals for their later years while they are young. It’s my intent to suggest ideas and approaches to guide our young ones toward an exciting life of learning, away from the disasters of addiction and harmful pursuits. Even though there’s information for the first-time grandparent that might not be needed for more than a decade, by being very intentional in “seed planting” throughout childhood, we can increase the power of our impact. For the experienced grandparent, there are new ideas and information to support grandparenting from the grandchildren’s present age into young adulthood. Regardless of the starting point, the plan is to share concepts and encourage influence and memory making from the nursery to college and beyond.

Special Opportunities for Grandparents

To foster their love of learning

As we hold the sleeping newborn, we contemplate the wonderful adventures we’ll have, the exploring we’ll do, and all of the learning we will experience together. In just a short time, we’ll teach this little one to stack blocks, to catch a ball, and to enjoy the books that we’ll read together. We smile as we anticipate all of the exciting time our relationship will bring. Then, we think about how precious this little one is and how important and productive the learning will be.

Making Time for Opportunities

Expressing unconditional love, caring, and interest is easy when all the baby does is look at us, coo, and smile. It’s easy and great fun to clap and encourage when baby is able to roll-over, takes those first steps, or stacks one block on top of another. We can be generous with our encouragement during these early days. We can be liberal with our applause for the cute toddler, especially if we can return the child to the parent for any difficulties. Our challenge is to continue the expression of unconditional love and finding ways of communicating interest and encouragement as the child grows.

By the time the grandchild reaches what’s sometimes known as “the terrible twos” stage, we may wonder what happened to the cute baby that we could cuddle in the rocking chair. Instead, we’re faced with an often cranky, constantly in motion kid who is said to have a vocabulary of 200 words, but only says one—“NO!” At this point, it becomes easier to be busy when we’re asked if we’d like a visit from the little monster, or to simply proclaim that we don’t have the energy to provide a safe environment. We could just suggest that pictures be sent instead. It seems like the easy and smart way to simply wait until the child is older to see if we really like this kid because it’s certainly different from that adorable infant who delighted us only yesterday. Although we joke about such reservations, we do secretly hope the child will become civilized so that we can begin to live out the imagined activities that we expected to have with this “whirling dervish” that may carry our genes and hold our hopes for the future.

While it’s easy to abdicate all activities to the parents at this time, it’s really the wrong decision. Just as when our children were this age, the stage of beginning independence must be encouraged and also endured. Although much patience may be required, it’s essential to remain in contact with the two-year-old and continue cementing our relationships. It isn’t possible to take a time-out in our relationship building just because we don’t relate well to that age, or that they’re too much trouble at that stage. Rather, it’s essential to continue to build our bond of guidance and nurturing, regardless of the age or challenge.

Sometimes, it’s easy to allow our opportunities for learning and making memories to degrade into child care, just watching the grandchildren to be sure they’re safe, without much thought as to what they will do while with us. Anyone who’s tried this approach has probably learned that, if we don’t focus their activities, they’ll make their own—not always the best for them or for us. Instead, it’s more productive for everyone if we plan our time with the child. For example, we don’t invite a friend to visit, and then just try to ensure his/her safety. We don’t invite one of the guys over, turn on the TV, and ignore our friend. Instead, we invite friends to lunch or dinner, to watch sports, or to do something. When we issue invitations to others, it’s usually with a purpose, plan in mind, and we interact with the guest. Visits from the grandchildren should not be different. They need a reason and activities for every visit.

As indicated in Chapter 2, ideal grandparent time is one-to-one. These focused interactions are impeccable for building influential relationships at any age, but can make indelible impressions on young children. If grandparent time is limited, or restricted by geography or other circumstances, it may be necessary to see several grandchildren at once and with more than one grandparent; however, that may not the best possible arrangement. Since part of the magic of grandparent time is the focused attention, it’s easier and usually desirable to see one grandchild at a time. At least some the time should be with just one grandchild and one grandparent. If two grandparents are together, the adult focus may be a distraction from the child focus. If there are two or more children, they may compete for grandparent attention.

(Pages not included here)

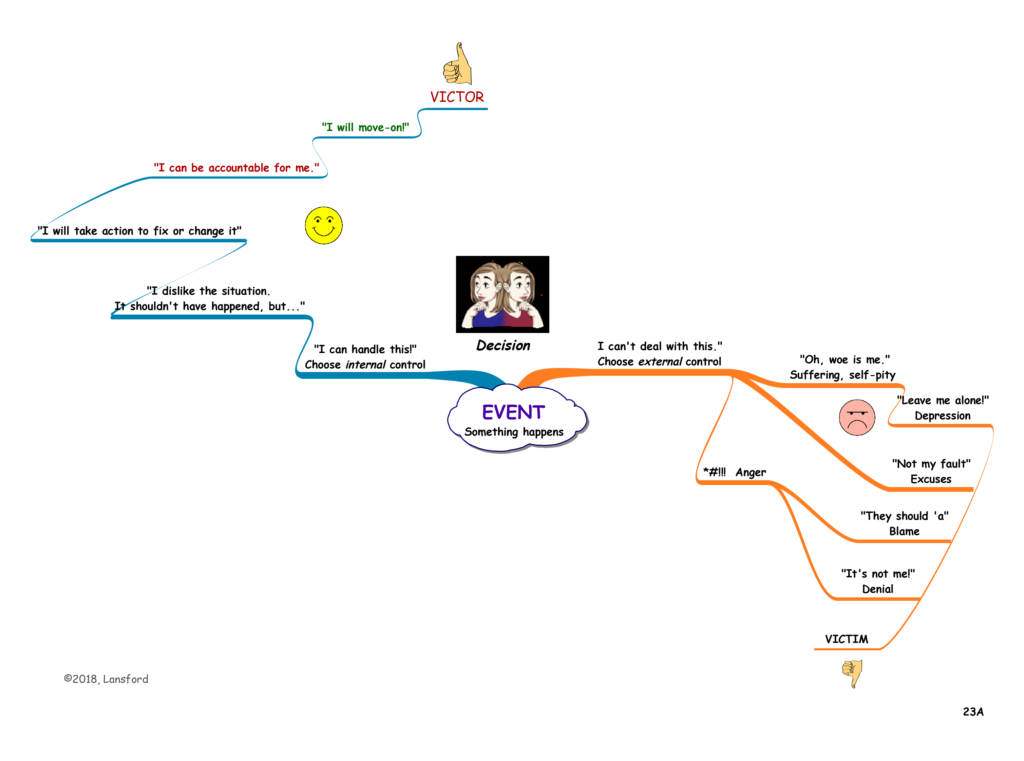

I’ve often wished for a valid way to measure self-worth. Then, we could determine if there’s a statistical significance between low self-esteem and addiction, i.e., “I need the cocaine high to compensate for how I really feel.” Perhaps it’s essential to help children recognize that they cannot always control what happens, but they can control what they tell themselves about what has happened. We can help them sustain a strong sense of self-worth through self-talk that can become its own feel-good. This sense of control can make a monumental difference in results for the grandchildren throughout their life. Even though we can’t always control the forces around us, we are free to choose how we react to what happens. We can choose what we tell ourselves about what has happened. Such a mindset is very helpful for us grandparents as we hone our skills in teaching grandchildren the importance of having positive voices in their little heads.

Chapter 6

The Instant Generation

As we strive to guard against our own defensiveness in the face of change,

Help us to develop a reasonable optimism when confronted by the new.

We can do everything to build and enjoy close relationships with our grandchildren when they are young. We can have long low shelves of interesting books and toys that capture their interests when they visit. We can play endless games of tic-tac-toe and chess. We can take them on trips to Disneyland, to the beach, parks, museums, and playgrounds. We can teach them botany and entomology while exploring the backyard. We can become very influential in developing their character. We can be ideal grandparents through childhood, and yet, lose them during adolescence.

It’s frightening how the children who cried and protested when having to leave or miss a grandparent visit suddenly have no interest in seeing us or even taking our phone calls. It’s sad when they scheme and complain that we’re so old and boring or that they just don’t have time for grandparents anymore. When this transpires, we grandparents cannot feel dismissed or alienated. We cannot sulk and express our pitiful feelings of rejection. Instead, it’s merely a signal that those cute little ones are growing up and that we must not become obsolete in their world. We must change our approach. At this point, their interests and needs for independence are growing exponentially. Just as we changed our technique and the environment that we provided when they learned to walk, it’s now time for other significant changes.

We must change the home activities. Instead of having toys on the special shelves, we must have different board games and content, such as classic books to discuss or new apps on our phones that help us connect with them. The chess set that was used when they were young should continue to be a challenge as their thinking skills develop, but a more mature edition may be needed. The National Parks or Metropolitan Museum Monopoly and other versions may continue to capture their attention occasionally. CandyLand, and Mouse Trap, however, may need to be replaced by Diplomacy, Apples to Apples, or other games.

Although we might miss the enchanting afternoons of sipping camomile tea from the Peter Rabbit tea cups, the menu may need to change to popcorn, lattes, and food that pleases their taste for accompanying grown-up style conversations. It’s important to think of interesting topics and thought provoking questions to have ready for their visits. Just as the face-to-face and eye-to-eye conversation with focused attention was important when they were five, it’s equally essential when they’re fifteen or twenty-five.

It’s time to share more of the world in which we’ve lived, and at the same time, show them that we understand and are relevant in their world. It’s time to build our ongoing credibility. The credibility that was once achieved by ice cream cones and bedtime stories must now include a demonstration that we’re savvy and can relate in today’s world.

Grandchildren Live in a Very Different Era

In the nineteenth century, schools were not available for everyone, but parents could ensure their children acquired the necessities of a good life and would be successful if they taught their children a responsible work ethic, and to read and write. In the twentieth century, schools were larger, had a longer calendar, and took over the responsibility for teaching children to read and write, along with the acquisition of many facts about history, economics, literature, and language. In the twenty-first century, however, technology has changed what’s needed in the curriculum. Instead of acquiring knowledge, technology puts all facts at the fingertips of every student. Therefore, the schools are needed to teach the students how to find out and how to learn.

(Pages not included here)

Summary

It’s human to want to feel-good and feeling good can be addictive. The armor that will keep our grandchildren from being vulnerable to drugs, alcohol, and all sorts of things and people that will not be good for them, is to teach them from a very early age how to make their own “feel-goods and self-talk.” We can teach them the self-talk of internal control and responsibility that can be louder than detrimental victim talk. We can help them learn how to be in control of their own brains and their own mindsets. We can be sure they understand that choosing a healthy brain means freedom—being free from the disease of addiction and being free to choose their future.

When they’re babies, we can calm and soothe the grandchildren, gradually helping them to calm themselves. When they’re young, we can soothe and calm the unnecessary fears by showing them how to take action to reduce what’s making them sad or afraid. Most of all, we can be alert to childhood fears and lowered self-worth that might follow them into adulthood and reduce personal success. We can listen to the grandchildren verbalize their fears, help them solve problems, find actions they can take to diminish their fears, and calm the unnecessary fears. Regardless of how funny or ridiculous they seem, we make no contribution to the grandchildren by laughing at what they’re afraid of or trying to diminish what they don’t understand. Instead of disregarding their fears, we use them as opportunities for learning.

When teenage grandchildren appear with straggly hair, tattoos, piercings, or inappropriate and unattractive clothing, they may not give us a feel-good emotion. Sometimes, it seems as if an easy goal for grandparents could be to simply survive the period of adolescence and hope that the teens get through it with as few life changing events as possible—addiction, incarceration, pregnancy, or physical harm. It could be easy for us to distance ourselves. Yet, that may be when they need us most. Unfortunately, there’s nothing more potentially threatening to our precious grandchildren than being bullied into depression, going to school, out with friends, or anywhere, with a depletion of “feel-good” brain chemicals. With such a deficit, they may be tempted by the latest “party pill” and become vulnerable to underage sex, careless decisions, and getting their “feel-goods” from alcohol, nicotine, pills, or through a needle.

Perhaps a better approach is to make this another phase of development for thriving. In learning positive self-talk, and how to develop their own “feel-goods” in the brain, they become less vulnerable to addictive substances. If we have done all of the precursors well, perhaps teenagers can make that thrill and reward seeking of the adolescent brain into positive pursuits of learning, intentions, entrepreneurship, discoveries, and adventures. Adolescence is a time that, instead of being endured, can be nurtured and enjoyed by the grandchildren, their parents, and us.

Perhaps the result of good grandparenting is not just in attending to the children’s physical safety, or stimulating their cognitive development, but also being vigilant for positive biochemical maintenance. If we teach them how to create their own “feel- goods” and “self-talk,” then we can significantly reduce the likelihood of the ghastly crises of addiction. If we develop a loving, bonded relationship with them from infancy and plant the seeds of good character, resilience, and decision making, we will have shown them the path of virtue. By teaching them what to do when they’re sad and how to be in charge of their brains, and emotions we’ve taught them how to be free of addictions and in charge of their own lives.

In making memories that create good brain chemicals, we can make a difference in our grandchildren’s lives. We can ensure that they know how to deal with their fears, sadness, and anger, as well as how to feel and express joy, pleasure, and happiness.

Grandchildren’s Personalities

Help us appreciate and honor their differences.

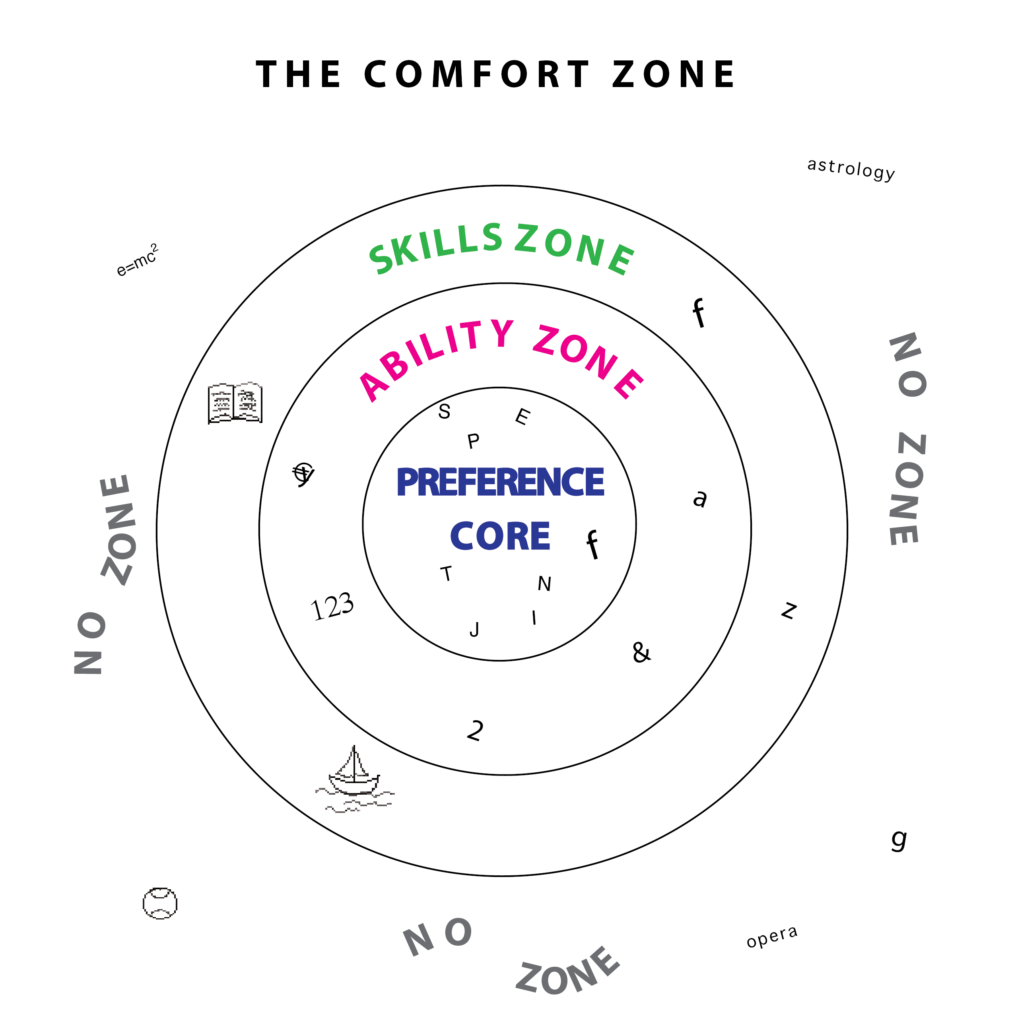

Sometimes, grandchildren’s personalities are similar to a parent or grandparent’s personality, but not always. It may be convenient and easier to relate to children whose demeanor, style, manner, and personalities are familiar and comfortable for us, but when they’re very different, it can be challenging. This is when our toleration and appreciation of diversity is required. Perhaps the quote attributed to Carl Jung expresses our challenge, “Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves.”

Considering a child’s personality and preferences not only helps us to better connect with the child, but it can help us nurture the child’s individuality. Even though it’s easy to develop chemistry with a child whose temperament is similar to ours, we must be aware of the child who is different. Maybe we’re aware that the affinity isn’t there, that the bonding doesn’t come easily, but we’re not sure what to do about it. The child may sense that difference and see it as disapproval or rejection, a situation we grandparents must avoid.

There are numerous approaches to studying the child’s personality, but perhaps the easiest is to simply be aware of our own preferences, of the child’s preferences, and how they are similar and different. We can just ask ourselves some questions about what we observe and how the child is like us, or not. Instruments listed in Appendix D can be helpful later, but may not be necessary for now. Simple awareness is the place to begin.

Exploring Preferences

Many factors make up the human personality—the type, set of emotional qualities, ways of behaving, etc., that make a person different from other people. Some are attractive qualities that make someone interesting or pleasant to be with, while other attributes may be less desirable or perplexing to us. We know that much of what constitutes personality is innate. We can even see it beginning to develop in the early part of the child’s life. Sometimes, we see what pleases us, the emotions or behaviors with which we identify. Other times, we may observe something puzzling, but this is part of the challenging delight of being a grandparent. This is an opportunity for our learning as we help to nurture the child’s development.

There has been considerable research into personality. It’s been studied and written about since the time of the ancient Greeks. There are numerous instruments and materials available that attempt to define personality traits and predict behavior. These systems range from labeling personalities with various colors to the online questionnaire that identifies you with a cartoon character, but these may be of limited use for our purpose.

Perhaps the best source for considering the budding personalities of our grandchildren and supporting their development comes from a century of what began with the Swiss psychiatrist, Carl Jung (1875-1961), and Americans, Katherine Briggs (1875-1968) and Isabel Myers (1897-1980). Through the subsequent decades of work at the Center for Applications of Psychological Type (CAPT) and Consulting Psychologists Press (CPP), Myers’ original research and development of the Myers Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI®), has been continued. Through The Myers Briggs Company’s publication of Myers’ work, the research has been extended, keeping the instruments’ language current, expanding the supporting resources available, and making the materials relevant and very useful for today. If you’re familiar with the key to unlocking Jung’s ideas, the MBTI,® these concepts will be easy to apply to understanding the grandchildren. If not, there are resources in Appendix D for learning more about these extraordinary tools for children and adults. One caution—don’t be hesitant about the original publisher’s name. This material is not about psychopathology or Freudian analysis. Instead, the instrument uses everyday language and is a simple means of beginning grandparents’ observations, awareness, and thinking about our special young people.

(Pages not included here)

My favorite example of this re-energizing preference is the party story. If you take two grandchildren to an exciting evening party where both engage in lots of activities, talk, and play with numerous other children, both having an equally good time; the difference is observed at home. The introvert will likely go home and be ready for bed immediately, eyes closed almost the minute the head hits the pillow. The extravert, however, may get into pajamas, but will insist on a snack and an animated conversation, recounting the people and activities of the party. The extravert has become re-energized by all of the interactions at the party, while the introvert used energy. In the quiet, and with the lights out, the introvert can calm and re-energize, gently falling asleep while the extravert needs to unwind because the child was so energized by the party experience. To deny either would be to deny their needs. Even though it may not be what we need, or what we think they should need, the attentive grandparent supplies the child’s needs.

Fast-forward to the teen years. If we want to know about the fifteen-year-old extravert’s world, who his friends are, what he does when away from home, and what he’s thinking, we may have to listen to endless childhood chatter from the extravert from the time he’s a toddler. For children with preference for extraversion, we become a great source of enjoyment and re-energizing when we listen intently to the stories and constant narrative of the child’s world. Then, as a teen, we’re likely to continue to hear about the grandchild’s world when that bond of engaging conversation was established early.

Conversely, it may seem convenient to have grandchildren who are introverts during the childhood years because they’re often happy to play alone, and they will leave us alone when they are in our care. The challenge comes, however, when they are teens. If we have not established ourselves as a supportive resource during their childhoods, if we have not gently asked open ended questions, and if we have not been patient with the pause before their responses; they will be less likely to share their concerns, activities, or problems. It’s easy to diminish the relationship with an introvert during the teen years.

(Pages not included here)

After thinking about our grandchildren’s preferences, we may become more aware of our own preferences—how they are like the child’s or very different from the child’s. When referring to romantic relationships, we often use the common axiom, “opposites attract.” In social relationships, we may be fascinated by people who are very different from us. Yet, the more exposure we have to others, the more that social comparison force seems to prevail and we want people to be like us. We’re comfortable with people who have a similar demeanor and attitudes. If they are different, there’s a temptation to want to change those differences, to correct what we may see as deficits, and to make them reflect well on us. Although we can accept or reject our social relationships, when it comes to grandchildren, it’s imperative that we accept them for the budding personalities that they are. As discussed in other chapters, just as we must help them to develop their skills—social, math, or physical—we must help them to understand their preferences and develop their personalities. Even though it might be convenient for them to be more like us, such as being more talkative or more open to options, we must help them develop their innate preferences and nurture their own individuality.

When Preferences Clash, Resulting in Family Tension

As we have emphasized, there is no good/bad or effective/ineffectiveness in the preferences. We all have some of each, but we use or rely on one more than the other. Negativity only happens when we attach criticism to the preference. It can be annoying for an introverted grandfather to have an energetic extraverted four-year-old granddaughter, or for a highly logical grandmother to deal with a sensitive people- focused grandson.

Even though life may seem to be easier when our grandchildren have preferences similar to ours, we are often challenged to love the different. This proclivity for being with people who are most like us, who do things the way we do, who seem to think the way we do, can cause us to reject those who are different. Instead of appreciating their uniquenesses, we can easily slip into the trap of concluding that their ways or ideas are wrong. When we reject such innate qualities in the child’s personality, we send bruising messages that are harmful to the child and damaging to our relationships. Although we would never do this intentionally, we can reject without realizing. When the child with a preference for feeling is upset about being left out of play groups or if the 13-year-old is depressed at not having enough “likes” on social media, we cannot disregard their concerns. If we say, “Oh, you’re just being silly,” we deny a part of their personality. Even though such superfluous worries may appear illogical to us, it’s better when we understand and say, “It’s so unfortunate that you feel hurt. Tell me about what’s happened.” Sometimes, people with a preference for feeling seem to have an insatiable need for approval, acceptance, and reassurance of being loved.

(Pages not included here)

Without understanding and commitment to honor the child’s preferences, this difference in preference can cause tension in other ways. A simple trip to the ice cream shop that was intended to be a surprise treat has the potential to become a stressful adventure if we aren’t aware of preferences. The late Otto Kroeger (1994) liked to joke that people with a judging preference “moan.” He indicated that they complain about everything, even the things that they like or want to do. I maintain that this moaning is caused by their agenda. It’s as if these judging preference people have an agenda that’s carved in stone. If I suddenly proclaim that we’re stopping for an ice cream cone, the little judging preference in the car seat is likely to respond with, “Why are we stopping? Will we be late getting to the playground? Mom says I’ve had too much sugar this week.” It’s not that the little one doesn’t want ice cream. It’s as if he must get out his hammer and chisel to re-carve his agenda that’s written in stone. If we don’t understand the preference, we wonder why we bothered. We’re annoyed with the unappreciative, obnoxious little moaner in the back seat! When we understand, however, we just smile and reassure the child that it will be okay. After a bit of moaning that we ignore, he’ll adapt, and we can continue on a pleasant adventure as he enthusiastically licks his favorite chocolate cone.

Children with the perceiving preference can be equally frustrating from their love of random options. Actually, they love different options so much that they can generate more options than we want to deal with. When I announce a stop at the ice cream store, I’ll get squeals of delight because, even though the perceiving preference has an agenda, it’s as if it’s only written in pencil on paper. Since it’s quite easy to change, there’s no problem, but yes, that is the problem. Before I can park the car, the little one is saying, “What about frozen yogurt? I like frozen yogurt. Do you like frozen yogurt? Or, what about soft serve cream? It’s good, but Mom says it’s messy.” And once inside, there can be endless exploration of the different flavors, especially if it’s a shop that (without the pandemic) offers tasting spoons. By this time, I’m wondering why I thought this would be a treat because I’m exhausted.

(Pages not included here)

The total personality is made of many qualities, emotions, and behaviors. We have only discussed four aspects in this cursory introduction to the fascinating journey of exploring preferences. As you have seen, these are very simple concepts, but with enormous depth and complexity. Here, we have only attempted to point to the importance of enhancing awareness that these little people have a distinct way of being in the world and that it may be like ours, or maybe not. Grandparents can extend the knowledge and experience with the MBTI.® Our observation process begins during the first few months of their lives, and although probably never complete, our recognition and appreciation for their individuality is an awesome discovery for us grandparents. By realizing how they learn, re-energize, take-in information, make decisions, and like their worlds to be, we supply needs and understanding that may not be available to them elsewhere. Simply recognizing their differences and being aware of their individuality can significantly enhance our relationships and our influence with them. At the same time, this knowledge becomes a stimulus to their development.

(Chapters not included here)

Every day is an opportunity for learning. Every day is a chance for us to help grandchildren turn their dreams into noble actions. Every day is a chance for making memories and being influential in our grandchildren’s entire lives—from the nursery to college and beyond.

A Few Reviews from Amazon

Not Just for Grandparents – “What a most thoughtful approach to such an important life role—the Grandparent. But immediately what I find relatable is how my role as a doting aunt is also important. A very well-written demonstration of first-hand experience, but also with qualified knowledge of interpersonal dynamics. So great to have a book like this to fill an obvious void—celebrating coming of age (older age!) and transference of values to the next generations. How to listen intently, how to ask better questions. For the benefit of all generations and really applicable to all familial roles. Definitely worth one’s time as a thoughtful read!“

Just for Me! – “My emotional attachment to this information makes me feel as if it’s written it just for me. I kept nodding my head and smiling as I read. It really is a “conversation” and a great one, that so many grandparents need to hear. I can’t wait to buy copies for my grandparent friends.”

The Positive Influence of Grandparents, A Must Read! – Every once in a while I encounter a book that surprisingly so fills a gap I didn’t know existed, which strikes a balance of insight and real-world recommendations. This is that book for current and to-be grandparents. Our experiences may not prepare us to confidently contribute to our grandchildren. Lansford’s mission with this book is to help prepare real people living real lives to influence their grandchildren to weather life’s challenges, benefit from experiences, and create lasting memories. She identifies how grandparents are uniquely positioned to encourage their grandchildren, and to help teach skills and practices that will serve children as they grow up. My experience reading this book was that it helped me to understand the role I play in the life of a grandchild I’m not in daily contact with. This is an important book. It is at times sober, but there are complications in life that deserve to be taken seriously. It is often illustrative of how different scenarios might play out. It is always positive in tone to help the reader to be successful in this strange endeavor of being a grandparent. This would make an excellent book for book clubs and reading circles for grandparents or even older parents of young children.

Well Written and Well Worth Your Time – Interesting and very helpful in learning to understand and relate to children. The chapter on their personalities was especially enlightening. The personal experiences of the author are touching and make the book easy to read. A must-read for anyone who desires to enrich the lives of the children they love.